Keyword Search of DC CFAR Pilot Awards (2011 - 2021): A Basis for Discussion

By Christopher Williams

The HIV/AIDS epidemic disproportionately affects racial and sexual minorities. Black Americans carry the heaviest burden of HIV of any racial/ethnic group in the US - 42% of all new HIV cases in 2019. Black women make up roughly 6% of the US population, yet account for nearly 60% of new HIV infections in US women. Black gay and bisexual men made up 26% of the 36,801 new HIV diagnoses among all gay and bisexual men in 2019. Black male-to-male sexual contact (MSM) is the most affected group in the US for new diagnoses, followed by Hispanic/Latino men and MSM.

In Washington, DC, Blacks/African Americans are approximately 46% of the city’s population. The nation’s capital is resource-rich (e.g. budget surpluses, rapidly expanding tax base) and more capable to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic than most large metropolitan cities. Still, DC has acute racial HIV disparities. Blacks/African Americans constitute nearly 70% of all new HIV diagnoses: Black MSM and MSM/IDU (34%), Black heterosexual women (16%), Black heterosexual men (9%), Black men and women other/risk not identified (10%), Black men IDU (1%).

Ending the HIV epidemic is a federal priority. Yet, major structural barriers persist. This research brief was prompted by conversations with advocates in the HIV/AIDS community in Washington, DC. We sought to understand how well HIV funding through the DC site of the Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR) addressed those social issues in HIV research. The CFAR program is part of the National Institutes of Health and advances a mission of multidisciplinary research approaches that involves “basic, clinical, epidemiologic, behavioral, and translational research to improve the prevention, detection, treatment and cure/remission of HIV infection” in the US and abroad. Health disparities research is a central principle, “Supporting research on prevention and treatment of HIV infection in underserved domestic populations and those who experience health disparities, especially in communities at high risk for HIV infection.” Community partnership is a key feature of CFAR’s mission. DC CFAR has awarded $3.4 million in pilot funding. We sought to glean information about racial and sexual minority HIV disparities and DC CFAR’s pilot awards using only the information available on its website.

Methods

We identified award recipients from the DC CFAR pilot award recipient website and the archive page. We copied the summary text for each application for subsequent analysis. We created a list of keywords associated with sexual and racial minorities, in addiction to general words such as equity and women. For archive awards, we relied on the publication date of the article as the year in our table.

Results

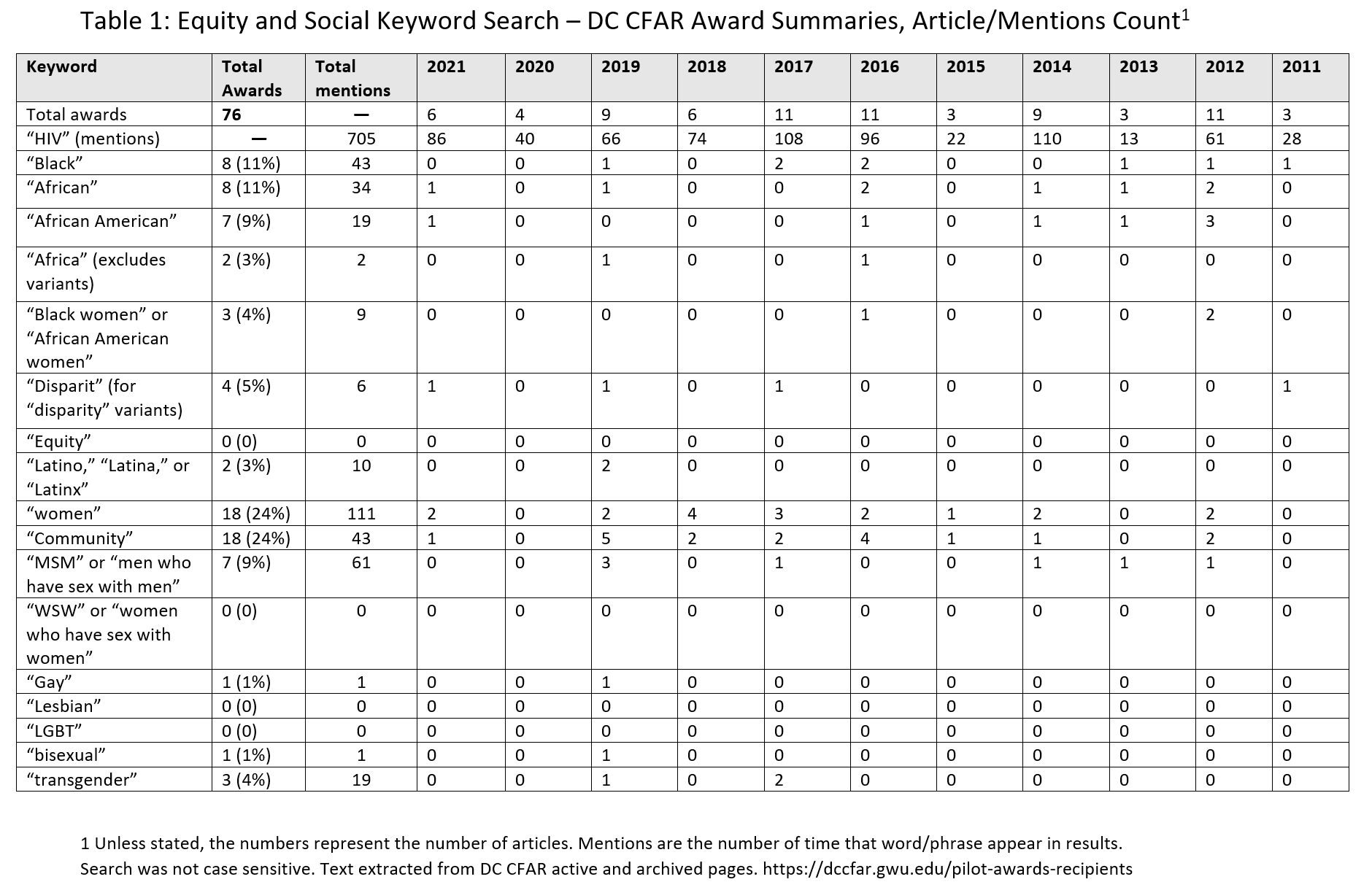

Our results generated 76 awards between 2011-2021 (Table 1). The number of awards per year varied from 3 - 11. Award summaries with ethnic words and phrases accounted for a small number of total awards: Black (n=8, 11%), African American (n=7, 9%), and Latino and variants (n=2, 3%). Article summaries with “women” and “community” appeared more frequently (n=8, 24%). Sexual behavior for men (MSM) was uncommon (n=7, 9%), while sexual orientation terms hardly appeared in award summaries.

Discussion

An analysis of pilot award summaries can be an efficient, low-resource research methodology. These summaries convey the core issues around which the research is directed and thus are a meaningful form of evidence about alignment with pressing needs in health disparities research. Our study findings raise major concern whether the needs of racial/ethnic and sexual minorities in the US and globally are being met in the current HIV research paradigm. We were most surprised that no awards were made between 2017-2020 that had “African American”. Most of those that were awarded (5/7) were between 2011-2014, despite the HIV burden for Black/African Americans. The awards for Latinx HIV research were equally abysmal. We do not understand why common minority sexual orientations (e.g. gay, lesbian, LGBT) do not appear or appear as a singular instance in 10 years.

This report sheds light on the potential source of CFAR funding as a source of structural health inequity. More study is needed to understand these awards more fully and how well the research is aligned with the multidisciplinary and translational standard that CFAR sets forth in its mission. This Public Health Liberation research brief is being shared with contacts at the national and DC sites as a basis for future discussion.

Sources: DC CFAR webite, Pilot Awards Recipients [source] [archive page]

Scroll below table for Update and Results of Secondary Search

Background: We received a message from DC CFAR saying that their research in racial/ethnic and sexual/gender minority communities was not capture in the abstracts. We conducted secondary analysis to compare with trends in Table 1.

Methods: We used "DC CFAR" and “District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research” in a PubMed search and general search online using the University of Maryland library digital services to identify articles. We downloaded all articles and conducted text searches using the same search terms as above.

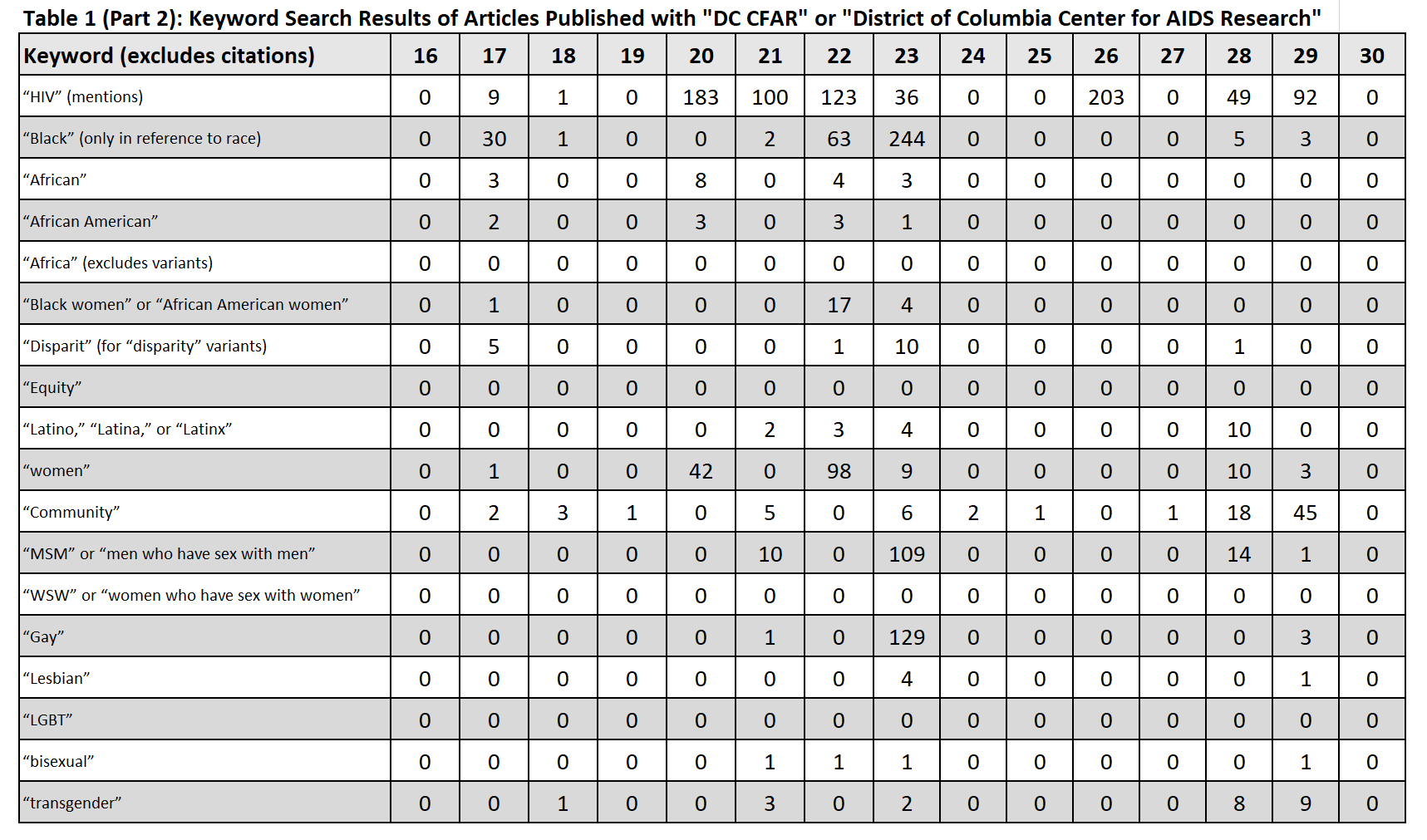

Results: There were 30 unique articles that resulted from the search. (List 1). Articles with terms about racial/ethnic (Black, African American, Latino, etc.) and sexual minorities (MSM, gay, lesbian, etc.) are infrequent. The central focus of the articles is reflected in the frequency of certain words. Predictably, “HIV” was common, although we were surprised by the number of articles that did not mention HIV at all or rarely. Where Black terms are mentioned, it tends to be in the study demographics section or to briefly state racial differences in outcomes.

Discussion: Our findings support the first study. Health disparities are understudied in DC CFAR research. This secondary analysis provides heightened concern that there is major deviation from the multidisciplinary and translational mission of CFAR.

List 1 - The 30 Studies Included in Study

Table 1 (Part 1 and 2) - Frequency of terms in full articles from university and PubMed search